Last April as I was coming home from a walk around the Scenic Loop in Cherokee Park I noticed a street festival on Longest Avenue in front of Heine Brothers. There were childrens' drawings of mountains strung across the street like prayer flags, live music on a stage bisecting the alley, beer and food sales, and mountain advocacy groups tabling in horseshoe formation along the barrier of Bardstown Road. I had the fortune of stumbling across Louisville Loves Mountains Day, an event that celebrates Appalachian culture and mountain life and raises awareness of issues threatening the vitality of the region. As I'm sure was the case for many attendees, this was my first formal introduction to the practice of mountaintop removal. I collected brochures and talked with KFTC members about the pressing nature of this cause, which cultivated my rudimentary support for ending mountaintop removal. I had a beer, socialized with friends who came to check out the festival, and tapped my foot to local music straight through dusk. That evening one of my friends commented, "I come from a family of coal miners. If they saw this they'd all laugh at the city slickers in Louisville trying to teach them how to live. Those communities have no choice, what would that region look like without those jobs? Everyone would be worse off than they already are. Mining is a necessary evil of that economy and way of life, you can't just erase that." In an instant I began questioning what I'd just consigned to. What I was witnessing at the festival; was this a gathering of voices for the voiceless, or a gathering of removed city folk with too much time and money? I realized that I didn't know the answer, I was ignorant to the dynamics of modern Appalachian economics and the environmental concerns of my fellow Kentuckians. Feeling confused, powerless, and angry with myself for being so clueless, my activist inclinations were ignited. I went home vowing to gain some answers. Unfortunately, in the typical fashion of detachment, I left the brochures laying around for a few days until I finally committed them to a place in the closet, and quietly tucked what I'd learned in the back of my mind. It wasn't that I didn't want to become involved, life just happened- studying for finals, working, doing research for classes rather than my own edification, music, drinks, and friends on the weekends- I lost my connection.

Almost a year has passed and still, until this past Saturday, coal issues in Appalachia were a distant glimmer of interest and intrigue in my mind, occasionally kindled by an article in the paper, a Facebook status update, or most recently the KFTC benefit at 21C featuring Jim James and Wendell Berry. On that evening Sean and I signed up to do a Mountain Witness Tour, an opportunity to visit Appalachia for a firsthand experience of mountaintop removal and its consequences on the culture and community. I will admit that even in the space between the fundraiser and the tour, I did very little aside from studying photographs to familiarize myself with the practice. I admit this for two reasons. One, it is the truth. Two, this is characteristic of an ugly facet of human nature, to be self-absorbed and immediate, unconsciously relegating peripheral concerns to matters of convenience.

Saturday was the day that forever absolved me of that habit. The following is my account of the Mountain Witness Tour in Whiteburg, KY on January 23, 2010.

We were on the road as the sun was rising. Muted brushstrokes of pink and orange divided the horizon of the road from the low-lying white sky. Dense fog masked the trees lining the highway, offering only a quick glimpse of the landscape from the window, blurred at 70 mph. We had a three and a half hour drive ahead of us to Whitesburg. A southeastern Kentucky town on the Virginia border with a population hovering at 1500, a quarter of which live below the poverty line, Whitesburg is rich in cultural significance. We knew we were in Eastern Kentucky when we began picking up WMMT, Mountain Community Radio, in Hazard. Gritty old-timey melodies welcomed us to the mountains, reprogramming our senses to a simpler frame of mind. The station broadcasts from a 40 year old arts and educational center in Whitesburg known as the Appalshop.

Built in 1969 during the federal War on Poverty project, the Appalshop's original purpose was to teach filmography to residents in the hopes that they would document Appalachian life, exposing rural Southern culture to a national audience. Today, the organization is responsible for hundreds of films, educational initiatives, theatre productions, publications, and the genesis of WMMT. In addition to boasting the Appalshop, Whitesburg also hosts an annual Mountain Heritage Festival and is home to the highest peak in Kentucky, Black Mountain. This was to be the site that forever changed my sense of civic duty and Kentuckian pride.

Our itinerary for the day was a curious balance of formal and informal; meet and greet at the Post Office, hike on Pine Mountain taking Bad Branch Falls Trail, a visit to the community of Eolia, mountaintop removal tour on Black Mountain, debriefing and strategy session. I wasn't sure what to expect, and to be honest, I was afraid to face my own sense of duty. I knew that whatever I was embarking on, it meant gaining the type of knowledge that comes with responsibility, the kind that imposes a moratorium on passivity.

When we pulled in to the Post Office we were greeted by a young energetic Columbian woman named Patty wearing a green KFTC hooded sweatshirt and brightly colored knit hat with bobbing tassels. A Whitesburg resident and KFTC organizer, Patty was inviting and eager, but still efficient and professional from the start. There were six on the tour in total, and her energy set a great tone for the rest of us.

Patty suggested a bathroom break before heading to Bad Branch Falls. Rather than congest the Post Office restroom, we dropped in on the Webb family up the road. Patty was positive that this would be a welcome visit, but confirmed over the phone as we drove up to a dirt and gravel driveway lined with plastic pink flamingos and a pack of six or seven happy country dogs. There was a log cabin home to our right, the stone ruins of a small structure to our left, two rustic cabins on a hill back in the woods, and a cabana at the edge of a lake in the middle of the property equipped with a smattering of rafts and canoes, even a pontoon boat. Wild yard ornaments were as bountiful as trees; CDs hanging in tree branches as reflectors, a rusted metal sculpture of a waving tin man, a mobile of braziers hanging from the ceiling of the cabana next to Jesus giving the thumbs up. A hippie-folk-art-back-to-nature retreat that the two giant pink-flamingo shaped signs at the gate dubbed "Wiley's Last Resort."

The dogs followed us up to the house, politely wagging tails in exchange for pats on the head. We were greeted at the door by a small-framed woman with long white hair who immediately rushed us all in to her home, eager to introduce us to the bat that had been hanging on the door frame above her living room couch for a week. It was hanging by one foot, or one wing, unphased by the commotion of its human audience. "The dogs don't seem to stir him either, " she reported. "Jim's not home, so I'm just going to take care of it myself. I've been watching these vampire movies lately and at first I wanted to let him be, but now it's starting to give me the willies." With glove in hand she presented a small bucket filled with leaves intended to house the slumbering guest. "I think I'll put him in the closet, or maybe the basement. Too cold to put it outside." With that she climbed on the couch without trepidation and attempted to reach the dangling creature. We all watched in a combination of good humor and confusion, Patty warning her that she may need help, maybe someone taller. There were a couple more unsuccessful swipes at the bat and the next thing I knew Sean was wearing the gloves with Mrs. Webb offering the open bucket below him. In an anti-climactic swipe of the hand, Sean was able to gently transfer the animal. We were all so engaged that it was hard to think of this as our first visit to the Webb's home, it unfolded more like a lively exchange between neighbors.

Some lively bat-related chit chat and a series of bathroom breaks later, Jim Webb came home.

Poet, playwright, politician, radio personality, mountain man, kooky old hippie, "Wiley Quixote," Jim Webb is one of the most unique people I've ever encountered. His white beard is as long as his wife's white hair. Doning octagonal red lensed sunglasses and a purple Black Mountain activist t-shirt, Jim gave us the "nickel tour" of his property. The landscape has changed quite a bit just since he took ownership due to three mysteriously spontaneous fires. He named it "Wiley's Last Resort," because when it's gone, there'll be nowhere else for him to go. Perhaps not coincidentally, he often referred to it in jest as the end of the universe.

The two cabins on the hill were built by his great grandfather in the 1830's, one was the birthplace of both his grandfather and his father. In it stood two vintage KFTC rally boards, one which read, "Stop the Broadform Deed."

The Broadform Deed was a law that allowed mining companies to purchase land for purposes of excavating any natural resource, above or below ground despite who resided there. This law set in to motion more than a century of pillaging, corruption, displacement, and destruction. The Broadform Deed was the first vehicle of cultural as well as environmental rape in Appalachia; tearing families apart, burying homesteads, and solidifying a system of economic oppression. The law was more or less reversed by 1984, but by then coal companies owned all the land and surrounding business, as well as the law enforcement and local politicians.

Jim's nickel tour put us slightly behind schedule, but provided an invaluable perspective of local politics, history, and hospitality. I am convinced that the day would not have had the same impact without his stories. He shed light on property laws, how mining company rights and landowner rights have changed and evolved, and why the relationship is so contentious, all with a unique manner of friendship and hospitality. Jim embodies what it means to be a kind soul and good neighbor, a man free of suspicion or prejudice. We were invited back to the Last Resort for camping, swimming, or hiking any time, and we will most certainly oblige. The Webbs offer their land to camp for free, all by word of mouth and honors system. He encourages donations and also loves to barter camping space in exchange for clearing paths and building new sites. There's so much to say about him that I can't rightfully articulate. For more, his website is http://www.wileyslastresort.com

From Wiley's Last Resort we drove to Bad Branch Falls which is located on Pine Mountain. This is where the work of the day began. Patty explained that the reason for our 40 minute hike to the Falls was to gain an appreciation for the miraculous natural environment that is biding time to destruction.

Our hike was spectacular. Bad Branch Falls, even in the winter, is lush and verdant, with shrubbery and small topiary reminiscent of the wetlands sprawling at the base of tall prehistoric trees. Lime green moss grows thick on the north face of trees and boulders The air is crisp and has a fecund, piney scent.

Along the trail there was a crystal clear stream rolling over rocks and branches, with the sound of rushing water growing ever near. When the falls became visible over the top of the hill it was breathtaking. A snow embankment at the foot of the water still powdery in the unseasonably warm weather created a mystical illusion. There were pockets of ice in the rock and on the other side of the falls a crystalline pond of ice blue pooled in an earthen crevice. There was mist spraying up from the snow and rock, framed in red sandstone and forest green.

Sean and I have been hiking in many amazing places; we've explored the Smokies, the Blue Ridge Mountains, and several National forests and recreation areas... This hike stands firm in the ranks of the most beautiful. Before ever seeing the leveled top of Black Mountain it was clear to me that reclamation could never come close to approximating recreation. There is simply no way to replace hundreds of thousands of years of evolution, biodiversity, and layered growth. With this knowledge alone it is apparent that reclamation is a shameful lie, and that mountaintop removal is an irreversible desecration of all that is sacred and pure. No photograph, no brochure, no lecture or rally could teach that the way Bad Branch did.

One defense of strip mining is that the process of reclamation will restore the mountain to its original condition. Reclamation is an effort to ecologically stabilize and restore a site after mining efforts cease. The mining industry is required to dump topsoil and trees in to valley fills for reuse in reclamation, though it is much more common for the company to be granted waivers absolving them of restorative responsibility. In the few cases that reclamation does occur, a thin layer of topsoil over hard rock will not sustain any kind of foliage, muchless wildlife, and in most cases topsoil is never redistributed to begin with. Millions of years of biodiversity is lost.

Biodiversity is not all that is lost to the greed of the coal industry. A drive through Letcher County will reveal three prominent enterprises; vacant lots, fast food, and gas stations. Economic diversity is an obvious casualty. Coal companies bear all the purchasing power, and to keep wealth from reaching the citizens companies buy all of the available property. Much of this property sits vacant, while existing structures are usually outfitted with fuel pumps and neon Kwik-stop signs. Very few residents have the income to compete with coal tycoons, which means local business is virtually non-existent. Employment options outside of mining are extremely limited. Compounding this problem is the popularity of mountaintop removal. It is the fastest and cheapest method of mining, which means jobs are short term, worker lay-offs are exponential, and property owners are left homeless. Many who are laid off end up with company-owned 7/11 jobs or turn to unemployment. In an effort to give back the community, once or twice a year the company will engage in outreach by distributing turkeys to poor families at Thanksgiving, or school supplies to children in the Fall. This cheap consolation (or is it flagrant placation?) echoes half-hearted attempts at reclamation, some kind of sad charicature of goodwill. However, residents rarely see it that way, as miners rarely work in their own region. That detachment, combined with heavy lay-offs, prevents folks from recognizing coal's impact on the local environment and eliminates the possibility of unionization. Patty elucidated this vicious economic cycle on the drive from Bad Branch, which must have revealed upwards of ten gas stations in a five mile radius.

Our next stop was Eolia, to the home of Sam and Evelyn Gilbert.

Sam was to be our guide up Black Mountain. A long time resident of Letcher County and former strip miner, he was familiar with both the procedure and the consequence of strip mining and mountaintop removal. On the way to his house Patty pointed out a bend just past a small community playground where she once encountered a family of bear while driving on the road. Bear sightings within residential areas have increased dramatically as they're forced out of the woods by blasting zones. When we got to the Gilbert home, that phenomenon was confirmed by Evelyn, who has watched bear pass by as she sits on the back porch. Set back in a "holler," the Gilberts own a stunning yet simple cabin-style home with a sprawling enclosed sitting porch. Lined in windows, it is bright and cozy, complete with dining table and couches. Up their drive are several dog runs where Sam houses his 16 or 17 hunting dogs. The Gilberts once raised 75 dogs and over 3000 quail. The quail were Sam's project, his attempt to restore nature with what he'd taken from it over years of small game hunting. They ate a lot of quail that year, the dinner table survivors released to the wild. Sam and Evelyn humorously agree that it was their first and last foray in raising foul.

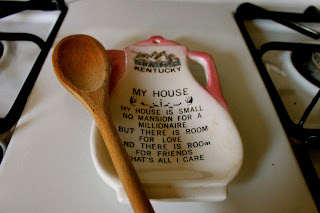

The Gilberts' welcome was every bit as filial as the Webb's. Evelyn greeted us with wet hair and bare feet, just out of the shower, again as if we were neighbors from up the road just dropping by. Their home was warm. Fresh laundry competed with apples and cinnamon for olfactory domination. Evelyn got us settled in and soon after Sam came to join. Evelyn has curly red-auburn hair and a genuine, maternal smile. Sam is tall and broad, an imposing stature, a solid and stoic exterior. However, once he sat and began to speak, his image softened. He told his stories plainly, without embellishment or bias, but with sensitivity for the land and residents. His career in underground and strip mining makes him an authoritative source, and a compelling voice against mountaintop removal. He got out of the industry as mountaintop removal was being introduced, citing the destructive nature of the practice (burying headwaters, demolishing communities, eliminating wildlife, further oppressing and enslaving mountain people, etc.). An anecdote about the time he dug a new well illustrated the toxicity of coal sludge seeping in to the earth. Typically wells are 100-150 feet deep, but Sam dug 230 feet to ensure a fresh and abundant water source. What he pulled from the hole was a urine colored liquid with an intolerable pungency. He had the "water" in a bucket one evening as he was working near a flame, and it actually caught fire and burned. This is the same water families have depended on for centuries for drinking and bathing. Now he and Evelyn must drink bottled water and depend on an older, less abundant well for washing. When that runs out, as it has in many communities, they will be bathing in water contaminated with mercury, arsenic, iron, and a number of other heavy metals and toxins. In fact, Patty knows a family with small children who must bathe from a contaminated water supply, all of them riddled with health problems.

Sam's bone to pick with mountaintop removal doesn't end at flammable water. In 2005 Sam noticed a strange truck parked on the edge of his property, which is at the base of Black Mountain just below a natural pond. After calling out several times without a response, Sam relied on a few blasts of his pistol to stir the elusive caller. He was immediately greeted by a man, all smiles, emerging from the hills to tell him that he was sent by the Army Corp. of Engineers to assess the stability of the area and the pond. The man was promptly run off the property and told not to return unannounced. After further investigation, and with the help of KFTC (where he met and befriended Patty) Sam found out that the coal company planned a mining zone on the mountain just behind his property. They were surveying the site of the old pond for use as a coal sludge pond. These ponds are located at the base of a valley fill to collect run-off and sediment from the leveled earth above. As water trickles down the mountain and filters through the mass of blasted material it picks up toxins and metals from dynamite and heavy machinery emissions, pooling in to a mass of poisonous sludge. Though the sludge pond is walled to keep it from washing in to the community, it is well-documented that these protective walls erode, erasing entire towns from the grid. Even when pond walls maintain structural integrity, sinkholes and shifted foundations are common consequences of such engineering.

The sludge pond proposal on Sam's land encroached on his property line by 100 feet, butting the pond right up against his home. Knowing that such a plan spelled the eminent deletion of his homestead, Sam partnered with KFTC to fight the coal company. The hearings went all the way to Federal Court that election year. Sam's tenacity and the people power behind KFTC led to a victory over the coal company. They're not allowed to revisit his part of the mountain for mining for many years to come.

For a more in depth description of Sam's fight and his critique of coal: http://www.kftc.org/our-work/canary-project/stories/sam-gilbert

It was humbling to be in the presence of such a dynamic figure, and I felt extremely fortunate to be viewing Black Mountain under his watch. Unaware of the condition of the mountain following all the snow, Sam grabbed his chainsaw and directed us outside to the truck. He chided Patty about taking her little sedan up the mountain and insisted she drive his Blazer. At that point I should have known we were in for a rugged ride, but I was still envisioning the nice mountain roads of Blue Ridge Parkway. We followed behind Sam's pickup to the base of the mountain. When I saw the road before us I was aghast.

It looked impassable. Jagged wheel ruts were carved in compacted dust and rock along a road just wide enough for one pickup. To the left was the wall of the mountain, to the right a long, life threatening look down. We were tossed all over bumping and maneuvering past low lying limbs and potholes at 5 mph. There were times that the turns were so sharp it looked as if one wheel would have to liberate itself from the edge. We all clung to the doors and busied our racing minds with nervous laughter. The craggy passage we were negotiating was a county road. Citizens' tax dollars are supposed to be allocated for road maitnance, but it was clear that the government did not want this road to be accessible. The treachery of roads near active mine sites is another mechanism of shielding the public from the extinction of their landscape. Patty, aware of our disbelief, said, "You are bearing witness to a crime. You can't just let it go."

That resonated with me rest of the evening driving through that mountain. Criminal on so many levels. Environmental wreckage, an economic hostage situation (Sam's words), withholding tax money, ignoring infrastructure, stealing land, monopolizing a job market, contaminating water supplies... It all swirled in my head as I already began trying to find the words to describe it to people back at home. But how? How to do justice to the magnitude of desolation, of corruption?

I was only half present in conversation for the rest of the way to the top, lost in my own heavy heart.

The scenery to the top was depressing. Dry straw-like grass spottily covered the landscape, splayed like puzzles pieces amid patches of dust. This looked like the desert, with pathetic spindly trees sporatically placed, clinging to life, roots a little more exposed with each gust of wind. The only thing not poised for disintegration was rock.

When Sam pulled over, indicating a good place to look out in to the valley fill, I secretly prayed that the ground beneath our wheels didn't crumble at the edge of the road. We emerged from the Blazer looking out over a rock-lined stream, the term for which escapes me. A long trough of rock constructed down the side of the mountain as a drainage mechanism, another band-aid gesture that doesn't stop contaminated run-off from seeping over the sides of the plateaued summit. At the bottom, in the center of the valley, was an active underground mine.

The mountaintops in the distance were all a shadowy evergreen, still covered in trees, a stark contrast to the balding sandy mound we stood atop. On it we could clearly see the strata of the mountain; a layer of rock, a seam of coal, all the way around. Before hopping back in the Blazer to continue our ascent, Patty told us that what we were surrounded by was reclamated land. The mining company had officially washed their hands of that side of the mountain. It was a prospect that just seemed unreal. This was their idea of stability, of restoration? I tried transplanting the image of the Falls on the hopeless visage before me. It was unfathomable.

Our next stop was the peak of Black Mountain, the highest point in the Bluegrass state. However, what Sam's truck stopped along was neither a peak nor a point, it was a dead stretch of flatland. We jumped out quickly because the sun was setting and we needed to get to the bottom before dark to make it safely. The wind whipped so strongly that none of us got too close to the edge. Being blown off was a plausible punishment for such brazen attendance. As I snapped photos the cold and the wind abused my knuckles, tore at my earrings, blew my hair over my eyes as if to say "Don't look." There was an eerie sense of isolation and abandonment gazing across the horizon on all sides at the sun setting over a leaf-capped ridge line.

We were all cold- physically and emotionally. It was time to make our descent.

Coming down the landscape began to change again. The road was less rugged, and the walls were lined in augering holes, not benches. Then heavy machinery became more prevalent, signifying an active mine to our immediate left.

We'd heard stories from Patty and Sam about being chased off the mountain by mining officials, they don't take kindly to people nosing around their crime scene. Patty proudly relayed stories of a few instances when Sam had to get stern with the miners, not backing down on one's right to pass through a county road. But we were no longer passing through, we were infiltrating. This was a company-owned, private road. It was possible to hear the blasting siren at any minute, we could be stopped and questioned, we were trespassing. At that news, the Blazer fell silent, as if hushing ourselves would make us invisible. Patty giggled and assured us that Sam knows how to B.S. right past these people, and that if we were to be stopped he would handle it. We were getting head nods and suspicious eyes from workers along the road. As we passed one truck we over heard a loud CB radio announce "It looks like there's a girl and a guy in the car." They were watching. I held my breath and tucked my camera under my jacket, unwilling to have it confiscated should an incident arise. My imagination ran wild with possible outcomes of this illicit journey down the other side, my trust for Patty and Sam being the one saving grace.

At the gate out of the site there were administrative trailers set up in a circle displaying banners espousing some moral mantra to the effect of, "Remember your responsibilities to family, co-worker, then self." Abandon your identity, it urged. When you're on that mountain it is in the name of family and company, civic and moral duty do not exist.

The signs made a lasting impression, though our minds were far from sublimated as we exited the gate, deceptively offering timid head nods and stiff waves to the guard as we passed. I exhaled. We made it down the mountain unfollowed, harassed instead by a lingering sense violation.

It has taken me over a week to put the Mountain Witness Tour experience in to words and still I don't feel like I've done it justice. An excerpt from my Facebook status that day reads:

"It is important for everybody to take this tour. I had no idea how it would impact me, but here are a few ways:

1. Right off the bat we were welcomed in to people's homes and treated as best friends and family... Sincere hospitality is a valuable reminder of how we should all reach out to one another.

2. Patty (KFTC leader) and our guides had a passion and willfulness that is inspiring to say the least. It's very empowering to hear stories of how just a few people can and have made big changes.

3. Experiencing the beauty of the mountains in an area that is untouched- We hiked Bad Branch Falls and were met with verdant foliage and a breathtaking waterfall.

4. As Patty said, "Witnessing a crime." Driving on a deadly treacherous mountain road that citizens' tax money is supposed to maintain. Traveling through "reclamated" land that barely grows a single spindly tree, and getting to the top of a mountain that looks like a fallow desert.

5. Feeling a tangible connection to a cause, a culture (our culture), and a community."

And that is the best I can do from my couch in the Highlands of Louisville, KY. Beyond my story there are several events just around the corner to stir folks' interest in mountaintop removal.

The first is Appalachian Love on Saturday, February 6, at the Green Building. This is a kick-off event for I Love Mountains Day. For more information visit http://www.facebook.com/event.php?eid=253271623638&index=1

The second is I Love Mountains Day on February 11 in Frankfort, KY. This is an awareness rally and lobbying day. For more information visit http://www.facebook.com/event.php?eid=237584639612&ref=ts

"Protest that endures, I think, is moved by a hope far more modest than that of public success: namely, the hope of preserving qualities in one's own heart and spirit that would be destroyed by acquiescence." - Wendell Berry

A great reference for understanding mining language: http://www.coaleducation.org/glossary.htm

Kentuckians for the Commonwealth: http://www.kftc.org

To schedule a tour: http://www.kftc.org/our-work/canary-project/people-in-action/witness-tours